This April 8th, let delight eclipse the darkness

2024-03-27

Dear reader,

We’re living in dark times. Pick any big topic in our world—climate, crime, war, poverty, cost of living—and the trendlines appear to be getting worse. We have data and more data to back up any concerns you might have about our future, and on top of that, graphic video coverage and photos from war zones around the world and horrible poverty right in our own towns.

When I experienced a bout of depression early in the legislative session this winter, there were times when I thought, “Maybe being depressed is a rational response to how things are going in the world.” In other words, my depression felt valid—I was only paying attention.

This felt true, and it felt important to stare into the bloody maw of life. But was it useful in the long run?

Looking to escape this rut, I’ve found a lot of traction in not following logic at every turn, but to also look for joy and delight, despite it all.

For example, Oliver, our two-year-old labradoodle, does not give up. He brings me a stick to throw. And while I might turn him down nine times in a row (I don’t have time!) he keeps trying.

Then, the tenth time, or maybe the hundredth, Oliver leaves a well-chewed hunk of maple in my path. Without even thinking, I size it up. It looks like it will heave well. I pick it up, throw it, and we’re off. Oliver’s love of life, like his leap, appears to defy gravity. I make room for this time with him, feeling that a small amount of light illuminates so much.

Poet Jane Hirshfield captured this in “The Weighing” (1994):

So few grains of happiness

measured against all the dark

and still the scales balance.

A total solar eclipse is coming to much of Vermont on April 8. It will be the last one visible anywhere near here until 2044. I’m excited to (safely!) look to the sky and enjoy this singular moment of darkness.

In these dark times, my intention for the event is to reignite my joy.

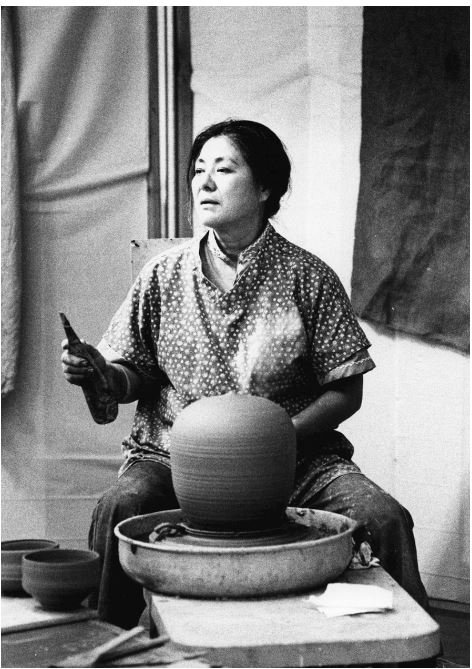

One of my greatest delights as a young child was making pottery alongside Toshiko Takaezu. Takaezu, born in 1922 in Hawaii, was a pioneer in American ceramic art. She began her career making ceramic ashtrays in a factory in the 1940s, and over her career she helped turn pottery into an expressive medium and not just a functional one.

But I didn’t know her bio then. I was a kid tagging along with my mom as she took art classes. With my brother, I had the run of the college art department where Toshiko was an annual summer resident.

Toshiko didn’t throw pretty bowls or utilitarian vases. Instead, I watched with fascination as Takaezu threw tall vases that she closed off at the top. Her closed vessels were punctured only with a pinhole to allow the hot air inside the piece to vent during the firing of the piece in the hot kiln.

Her final step before closing the piece was to ball up a tiny lump of clay, wrap it in newspaper, and drop it inside.

Watching her once, I asked—why the newspaper? She demonstrated how the paper prevents the wet lump of clay from sticking to the inside of the vessel. “It burns off when the kiln is heated,” she explained, shaking one of her vessels as an example. It rang like a bell.

Once a summer, Toshiko would devote weeks of work on her potter’s wheel to building an extra-large vase-shaped creation, often taller than me. I watched her close it off and—yes!—it contained a lump of clay just like the others.

Toshiko Takaezu at the pottery wheel, shaping one of her closed vessels.

In a world driven by science and efficiency and data, in a world of AI “art” that is both finely rendered and entirely derivative, such an act makes no sense. Not only was it a closed vessel with no use, it was too large to be shaken. Only a giant could ring it, I thought.

Then I imagined myself, giant-sized, shaking it for the whole world to hear. I giggled. And at that moment, my problems felt smaller. Toshiko’s lump of clay is an Easter egg, a delight of the imagination that still makes me grin decades later.

Fresh off the spring equinox and Easter, our experience of this eclipse gives us a chance to experience the sunlight and the darkness in a way few have seen before, and few will see again.

I invite you to ask yourself—What delighted you as a kid? Who were you before tragedy struck?

If we emerge from the darkness with more of these elements, the future will indeed be brighter, and in ways that we can’t logically see—yet.

Throwing sticks for Oliver in Halifax last fall