Play with your history

2021-11-08

Dear reader,

I’m afraid of talking about racism in public.

As a father and as a citizen, I need to do everything I can to understand racism. But I haven’t written about it. I’ve been afraid of having an incorrect opinion or unknowingly saying something insensitive.

These words feel wrong even as I write them. If I can’t talk about a topic, how can I understand it? With something as simple as directions to my house, I have someone repeat them back to make sure they understood.

This summer I was giving Isabel directions. A mile toward Brattleboro there’s a white house. The neighbor there has cardamom for me. Could she run down and get it for dinner?

As soon as I said “white house,” though, she thought of the nearest white house, which is in the opposite direction. Her mind latched onto that. And what else? Oh yeah, the neighbor there has a card for me.

Without dialogue, we are left with the quote in a friend’s email signature that always leaves me on tenterhooks, “The problem with communication is the assumption it has been accomplished.” – G. B. Shaw.

If I can't talk about racism I'm also less likely to see it.

How is it that old people can be so wise even though there is a steady downward line in cognitive function from 30 years old onward?

As you go through life, you have the opportunity to understand more, which helps you to see more. Seeing more helps you understand, and understanding helps you see.

My friend Bert sees more deer than me because he understands them. He sees signs of deer grazing around our old apple trees down by Pond Brook. He sees the copse of oaks on the far hill. He sees deer trails between the two. He puts these noticings together and understands the deer and their route.

Using these understandings, acquired over years of experience, he can sit and place himself in a position to see the deer. Laying eyes on them, he sees their coats, their antlers, their overall health. He sees their thick winter fur.

Then, a warm spell. He’s not seeing any deer. Where are they? Bert knows it’s too warm in their winter coats for them to be walking the miles in the sun from the apples to the oaks. He gets them. They’re hunkered down. He starts to imagine where that would be, and to put himself there.

So, this will be the end of when I don’t talk about racism. I want to see it, to understand it, and to heal the harm that has come from it. If I get something wrong, please understand I’m learning and let me know kindly.

***

I’ve abstained whenever possible from checking a box to indicate my ethnic background. I loved the poetry of Malcolm X who noticed when sleeping out in the open near Mecca that Muslim brothers of every color all snore in the same language.

But it’s also relevant to this story that I’m of Northern European descent, a.k.a., a white dude. All the way back to the Mayflower. I feel like it’s been respectful to do a lot more listening in the racism discussion than speaking, and so I have.

Well, in facing this fear I have found something I want to add.

That something is googly eyes.

Yes, those small round plastic things with self-adhesive backing. I gave a packet to my son as a stocking stuffer last year and we’ve been putting them everywhere ever since.

There are a lot of faces in your house already featuring a nose and mouth that are just ready to come alive with the addition of two googly eyes. The kitchen drawer handle. The detergent drawer. The clock face. Email me your address. I'll put a packet in the mail to you so you can try it.

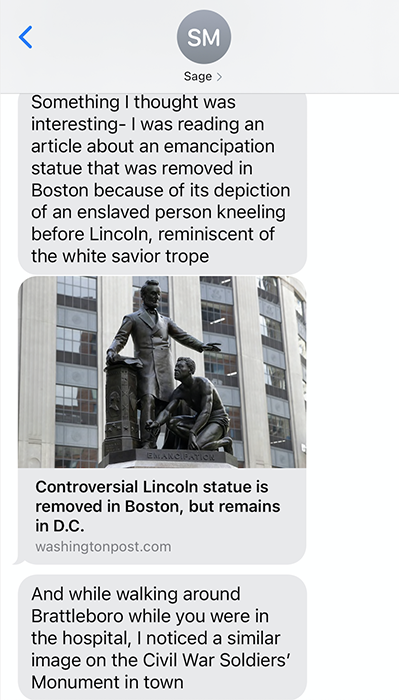

Even while the last few years’ debate over Civil War monuments was going on, I hadn’t given any thought to Brattleboro’s Civil War Memorial in the Commons. It was my friend Sage Mason who brought it to my attention in a text.

He wrote, “I was reading an article about an emancipation statue that was removed in Boston because of its depiction of an enslaved person kneeling before Lincoln, reminiscent of the white savior trope. And while walking about Brattleboro while you were in the hospital, I noticed a similar image.”

Sage had dropped me off at the E.R. the last time my shoulder dislocated and went for a walk around town. He came across the Civil War Memorial in the Brattleboro Commons, which indeed has a similar image to the statue in Boston.

I looked it up online. (I used a popular search engine that is named, if I’m not mistaken, for a pair of madly roving eyes.)

I learned that some Brattleboro students had recently drawn attention to another shortcoming of the monument. On another face of the monument, it commemorates 385 Brattleboro men who fought for the Union, and 31 who died.

Did you know that Black people fought in the Union army?

The memorial doesn’t. It leaves 60 or more Black soldiers out of the count, according to local researchers.

However, when my 10-year-old son and I visited the monument on Friday I was more focused on the five bodies depicted in the monument.

Give me a rifle, a Union soldier’s uniform and six months to groom my moustache and I could look like the guy standing proudly up top. Or the two soldiers on the side, one Union and one Confederate.

My friend Sage is Black. His body, his haircut, will never be mistaken for any person on this statue except the dude kneeling.

This memorial has angered some people enough to vandalize it. I can see why.

Every day this monument remains as is, Brattleboro endorses erasure. Black people fought and died to regain their birthright, their freedom, before the Civil War. During the Civil War. Ever since the Civil War. Yet the only monument in this park to the emancipation of Black slaves gives the white guys all the credit and all the dignity.

That’s brutal.

I see the most painful figure on this statue as the woman with outstretched arm. I assume she is Liberty. She seems so clear-sighted. She stands above the three men and sees past the horizon.

We gave her two googly eyes.

Now, both of her pupils swoop down away from her, in opposite directions. Liberty’s gaze looks crazy, and hopelessly lost. We couldn’t help but laugh at her. But I felt like we were also laughing with her.

Our country holds up ideals like liberty and justice and fairness. But these are ideals. Our real-life experience of liberty since 1887 has been more like the googly version. On some level Liberty knows this and is laughing with us. Maybe this is why her gaze stretches so far toward the horizon.

***

So much of what we need to understand about racism today is embodied. Racist words said or implied are part of the story, but our collective emphasis on words as a culture is arbitrary and overlooks much of our lived experience.

Before we put any of the googly eyes on, my son and I play-acted each person’s role. We each took turns kneeling like the Black person kneeling and receiving a scroll, which I assume to be the 13th Amendment.

“How does that position feel?” I asked my son.

“Awkward,” he said.

I stood before him in the position of the Union soldier handing him the scroll. (Which, I noticed, is ungenerously still in the hand of the soldier.) I asked him who was in charge.

“It feels like you’re in charge,” he said.

We stuck the googly eyes on the freed slave. (Some people deface monuments. We re-face them.)

The picture is all wrong. The Union reluctantly fought to keep the states together. It slowly realized it needed to end slavery and forced the South into this position. A more accurate scene might show the Confederate soldier cowering at gunpoint before two Union soldiers, one white and one Black. The Confederate soldier begs them to take the scroll. He asks for mercy and forgiveness, while doubting whether he deserves it.

On the monument, Lady Liberty is standing perfectly composed, every fold of her robes in place. It’s all wrong.

She should be dashing to the scene, her nightgown flapping in the wind. “I’m so sorry, I set my alarm for 1776 but I hit the snooze button till 1865,” she says. Afterward, she snoozes again until June 19, 1964, then again until May 25, 2020.

The googly eyes on the Black man reveal all this absurdity. Instead of standing in his rightful place, he’s kneeling and receiving some bogus piece of paper from his mom’s rapist.

“Whoa! Look! It’s a scroll thing!” as my son put it, with exaggerated enthusiasm.

Sometimes life is like that.

***

To undo this monument to racism, let’s consider whether it served a useful purpose at one time. Perhaps that will help the granite to yield more quickly.

The monument was put up by white people in power during Reconstruction. Did they depict the scene they needed to see, in order to live with the incredible changes that came after the war?

White people, including abolitionists, must have had complicated feelings about what it was actually be like to share civil society with slaves and their descendants. Many white people must have felt like they were giving up power, giving up wealth, giving up a way of life. This viewpoint is still present in some quarters today.

On March 4, 1865, his 41st-to-last day of life, Abraham Lincoln took the oath of the Presidency for the second time.

The war was about to end after five Aprils. His speech that day focuses on the work of the nation to complete the task at hand. He said, “Let us strive on to finish the work we are in to bind up the nation's wounds.”

What wounds was Lincoln referring to?

His concern was not the 4 million slaves that would be freed that year. He did not speak to their trauma, their poverty, or their future. His concern was holding together the nation he had gone to war to protect. That was a nation run, North and South, by white people.

In this context he uttered the words quoted on the monument, “With malice toward none with charity toward all.” This phrase stated a policy goal that the bloodshed and destruction of the war was enough. He didn’t want the South to be further punished by the terms of peace.

In line with Lincoln, the image of the monument not only preserves the pride of white people, it also preserves the power structure of white people standing over Black.

For these people to agree to the 13th Amendment, did they have to feel like they were doing slaves a solid, versus healing a wound their ancestors had caused?

The invisibility of BIPOC folks on the Brattleboro Commons enables this strain of thinking to remain present even today.

In order to put it down, we need to recognize the dated-ness of attitudes around “sharing power.” Our communities have many challenges. Many of our people are struggling, in many different ways. To support the healing, growth, and thriving of any one of us is to improve the strength and prosperity of the entire community. And as our communities become stronger, we all have more opportunities.

Power in a strong community is not a finite resource. Nothing has to be given up to include those who have been historically repressed.

I admire Frederick Douglass, who didn’t hesitate to use his voice. Brattleboro would do well to listen to his words in 1876, written in a letter to the editor days after the dedication of a similar monument in Washington, D.C.

Douglass wrote, “The negro here, though rising, is still on his knees and nude. What I want to see before I die is a monument representing the negro, not couchant on his knees like a four-footed animal, but erect on his feet like a man.”

It’s a good start. Let’s go further and build statues and art representing all BIPOC folks, all LGBTQ+, from all walks of life, and all ages, doing all the things that people do.

One of the best things about public art and performance is that it can give you new and different ways to feel your body, and to see the bodies of your fellow humans. I was unexpectedly brought to tears by the Moving Wall on its recent visit here.

Like the soldiers honored in that memorial, I want to clarify that I don’t feel any negativity toward Civil War soldiers, including those depicted in the monument. They served and fought for our freedom, as best as they knew how to do at the time.

At home, we often put googly eyes on family photos on the wall. It’s hard to not laugh when we see them on ourselves and our parents and grandparents. I appreciate my ancestors and what they did, but I’m also comfortable with the fact that every single one of them, down to myself, is flawed.

I have felt tense, anxious, and powerless about racism for many years. For me, the googly eyes have broken the tension of our post-Civil-War history. From here, I look forward to many more conversations and dialogue.

I see you,

Tristan

Quill Nook Farm