The last conversation with my father

2024-06-05

Dear reader,

“Starve ‘em to it,” my father would say, putting a staccato on the “to” and smiling.

“Ya just gotta staaaarve ‘em to it,” he repeated, chuckling. My dad was playing the role of Nelson Wells, the patriarch of the dairy farm next door to ours when I was a kid.

Nelson helped raise me, in a way. In my mother’s telling, I was an impatient breast-feeder as a newborn. I gulped the milk fast and furious, but I didn’t put in the time to sustain production.

Thus I was weaned within a couple of weeks on a bottle in which I was given the raw milk of Hyacinth, a red-and-white Durban cow. Hyacinth was the daughter of Annabel, the first of several cows my dad milked in our barn, and whom he took on “loan” from Nelson. (The loan, I later found out, was Nelson’s method for sequestering Annabel and her hoof rot from the rest of his herd.)

The milk that nourished me as an infant was redirected from a young calf who would otherwise be gulping it from Hyacinth’s teats. To achieve this, the farmer must, early on, switch the calf’s diet from the dam’s udder to milk replacement via bottle.

“Starve ‘em to it” was Nelson’s canny advice on how to make the switch, and my father recounted it ever since. Move the calf into another stall and offer it only the bottle. Its hunger soon compels it to accept the replacement.

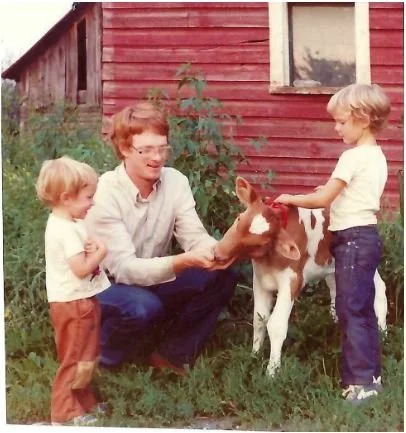

Me on the left with my dad, brother, and one of our Durban milking cows in Bacon Hill, New York.

Nelson’s been on my mind. Our baby is due August 3, and especially with it being her first, Alison is concerned about whether we’re prepared—for successful nursing, for co-sleeping, for all of it.

Also, we didn’t wait to grow. We have four adopted baby goats we’re trying to bottle-feed, and I’m desperate to find hay for our three piglets. I was told that this breed, Kunekune, is a slower grower that prefers hay over grain. That’s good news because hay costs less and can be traded with a neighbor. But I’ve given the two black barrows and one ginger gilt three different hay options and they won’t touch a hair on its chinny-chin-chin.

Should I “starve ‘em to it”? No can do. I may raise animals for meat, but I want them to be happy and loved the whole time. I hear them oinking as I approach. I see the untouched hay. They oink more. I give in, delivering them a scoop of grain—and then two for good measure. Where’s Nelson for advice?

More to the point, where’s my dad? I’m sad to share that even with both Father’s Day and my dad’s 78th approaching, Nelson feels closer.

“I’m Neil Roberts,” my father said to me last week, reaching out his hand. We haven’t spoken for three-plus years, but now and then there are encounters, like my son’s sixth-grade graduation last week.

How do you grieve a living father who forgets you exist?

“Hi! I’m Tristan Roberts,” I replied, shaking firmly, as he taught me. Did I see his face light up? My heart lifted.

“Nice to see you, Chris,” he said. Oh. He thinks I’m his brother. My heart sank. Here we go again.

Prior to Alzheimer's, my father’s parenting philosophy was as corporate as his M.B.A. As he explained in our last cogent conversation, “I was more of a manager to you before 18. Then I became more of a consultant.” A math major, he prized “rationality” and, like his engineer father, being “hands off.”

I loved growing up on a farm, wanted to create one of my own in Vermont, and at 27 I plowed the leftovers of my grandparents’ education funding into raw land in Halifax to make one. Rather than seeing that as a tribute to how he raised me, my father scolded me. Halifax in winter was “Hell on wheels,” he said. I should have spent the dough on grad school. “You could rent an apartment in New York,” he suggested.

Every visit from my dad used to mean three things. One, lumber, kindling, or something made from wood—his WoodMizer sawmill was his love language. Two, a ticking timer. I had better be prompt and gracious in my thank-you’s for any gifts, or he would become despondent and later send a resentful email. Three, incessant nudges to change.

“You should slow down,” he’d advise, before regaling me one more time with the story of shattering his left leg dropping a tree on it at around my age. He hung up his milking coveralls for good after that. His advice didn’t encourage me. It left me looking down at my legs and praying for deliverance the next time I picked up my chainsaw.

“Labor-intensive” was his term for my parenting. “You’re burning the candle at both ends,” he’d advise me as I set off for a two-hour stroll in the woods with my baby wrapped to my chest. He wasn’t wrong. I was working full-time, off-grid homesteading, and often popping out of bed five times a night to comfort our crying toddler. But I chose to believe that my son will thrive in independence as a man if he feels secure as a boy. Abundant love and presence is my biggest bet as a dad.

Each generation updates the art of parenting by trial and error. I’m sad about it, but I don’t judge my dad for his attempts. I’m grateful for what worked. In learning from what didn’t work, I can find my gratitude for that, too.

As a kid, I’d overhear my father say, “I want my sons to be an improvement on me.” Even as often as he noted my flaws, I assumed he meant that he was invested in my success. Now I realize he was more Old Testament. He made me and then retired behind the sidelines to keep score and be the final judge of “improvement.”

In that farewell chat, he had faulted my scorecard in relationships, going back to his recollection of my first adult breakup, at 18.

I responded with a smartass comment—“smartass” being one of my dad’s put-downs, the insult of a parent uncomfortable with a kid who wises up to a bad deal. “If I was an obvious failure in relationships by the age of 18,” I asked him, “around whose dinner table did I learn those skills?”

“Your mother thinks it’s in your genes,” he replied.

“And who gave me those genes?”

No, I didn’t say that last part. My smartass self was beaten. What to say to a father intent on closing out his account with you? What to say to any person who’s decided they’re better than you and feels better not checking their assumptions?

I’ll never find the key to that lock. Meanwhile, I’m glad I’m being a dad my way, and I’m glad you’re doing it yours. My plea to all parents and children is this—It’s never too late, and there’s never too big an issue, to offer an olive branch. Milk will always remain a limited commodity, but there need be no scarcity of love.

Now, I’m going to try moving the piglets to fresh grass. Happy Father’s Day!

Warmly,

Tristan Roberts

Quill Nook Farm