How I fell for the Afghan "war rugs" story

2023-06-16

Dear friend,

I've been a lifelong news junkie, since well before citizens of Saudi Arabia and three other countries not named Afghanistan attacked my country on September 11, 2001.

I've reading countless articles on the "War on Terror" since then. A small handful have been so resonant that I remember them years later. I'm going to talk about two of them today.

One wasn't about the war. It was a review of a gallery opening in the Times regional edition in 2014. But I found the story, Despite Conflict and Repression, Creativity, a compelling accompaniment to the front-page headlines.

Times article on "war rugs"

The article expected visitors to the gallery "to react with surprise," to the display of Afghan culture. The report quotes the the curator of the show Dr. Deborah Hutton:

“Most of the images we see of Afghanistan are the ones that are in the news, of the Taliban or of women in burqas. There’s this idea that there’s no culture left at all, which isn’t true,” said Dr. Hutton, 43, of Trenton.

The Times reports on a “surprising” way in which everyday Afghans were experiencing the War in Afghanistan. The article covers an exhibit at the College of New Jersey Art Gallery showing how weavers of traditional Afghan rugs had incorporated “the grim realities of life in a war zone into their traditional craft.”

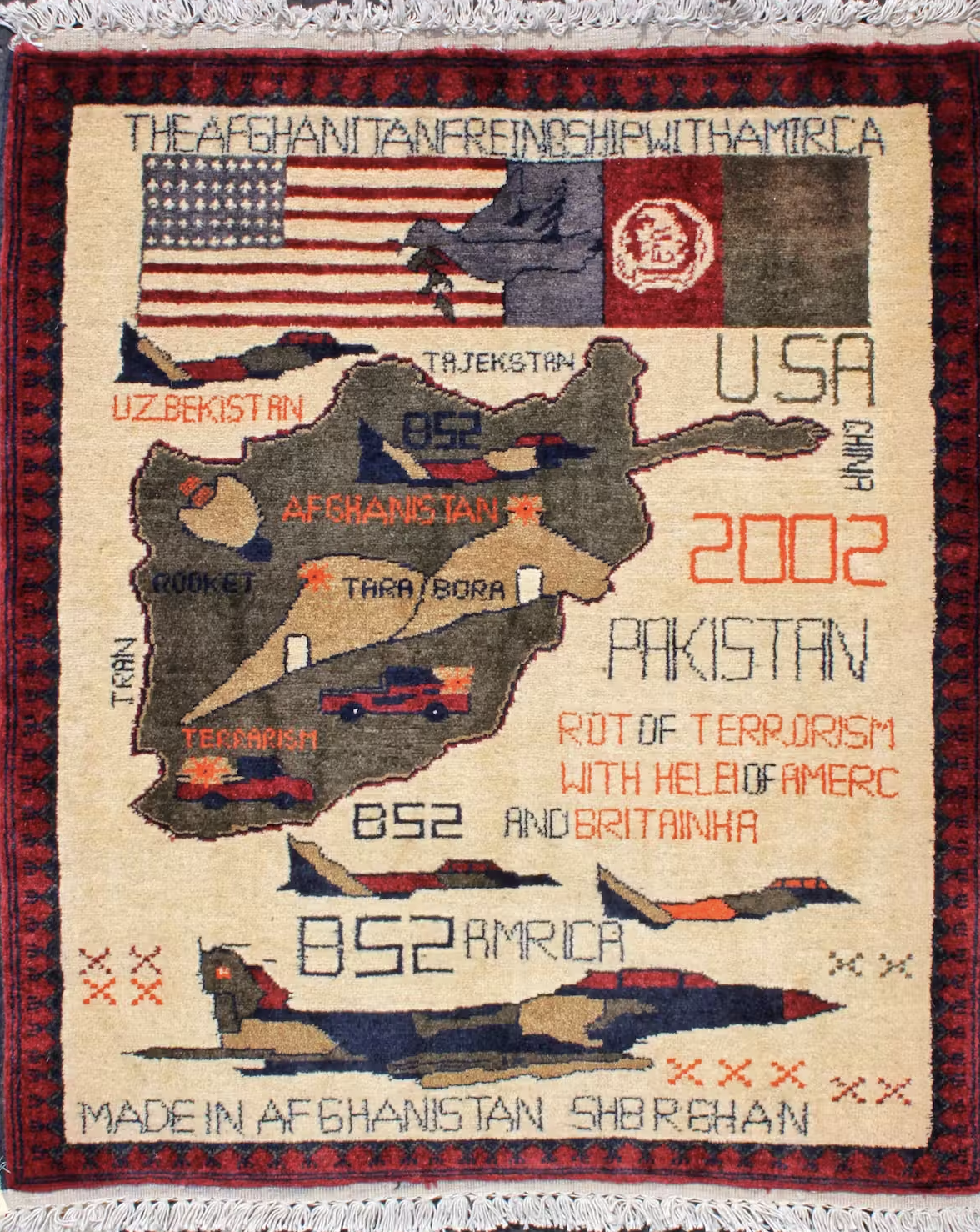

Drones, helicopters, soldiers, even an image of the Twin Towers on fire, were showing up in these rugs. The gallery had “acquired” examples to display. It weaves a narrative of the Afghan weavers as folk artists expressing themselves.

The 2014 article stuck in my head ever since. Maybe the rebel in me felt happy to see that regular Afghan people were doing something artistic in response to the war. I like to travel and seek out authentic art and craft. If I ever encountered rugs like this in a market, I'm sure I would have my wallet out.

In retrospect, I was primed for this response by an earlier Times article, from 2012, that impressed upon me how ill at ease residents of Kabul and other cities were feeling.

Ordinary Afghan people going about their lives had American drones in flight over them 24/7, ready to deliver a targeted missile against the Taliban. The U.S. military had a blimp floating over Kabul that gave it surveillance ability over the whole city.

Everyone was aware that the U.S. military was willing to inflict “collateral damage” on Afghan citizens in order to assassinate a key combatant or leader. An ordinary person could be struck by a missile at any time.

The most colorful quote from Spy Balloons Become Part of the Afghanistan Landscape, Stirring Unease is from Mohammadullah, a resident. Mohammadullah says in the article, “Whenever we want to say ‘hi’ to our wife when we sleep on rooftops, we feel someone is watching us.”

This vulnerability and perhaps humiliation left an impression on me. Reading about “war rugs” two years later, I thought, “Art really does imitate life!” I felt in touch with the gritty reality of the war and its effect on “ordinary people” in Afghanistan.

The newspapers know their audience. I was against the war, as were lots of Americans. I felt guilty that our foreign policy did not reflect my values. I was a willing audience for any media that helped me connect with ordinary Afghans. I might not be able to do anything concrete for the folks there, but I felt good as a human being empathizing with them.

***

Last year, in 2022, I was thinking again about the "war rugs" and did a little online research.

I'm concluded from that that my empathy for Afghans was fabricated as a product for westerners. I was suckered to buy it just like any other media narrative.

What broke the spell was a 2021 article by Jamal J. Elias, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania. In Afghanistan’s war rug industry distorts the reality of everyday trauma, Elias points out something that I feel I should have seen all along.

These rugs came to the U.S. because Americans living and working in Afghanistan purchased them. They’re souvenirs. They were probably a bargain. An artful, gallery-worthy bargain, but a souvenir made for the foreign market.

Most weavers of these rugs are women and children working long hours for little pay. They don't design the rugs. The content of the rugs is commissioned by middlemen whose job it is to achieve product-market fit.

Afghan rugs have been popular as long as I can remember. Then Russia invaded Afghanistan in 1979. A rug dealer had the idea of putting images of war in rugs and charging a premium. Collectors from western NGOs bought them. More dealers got in the game.

Artistic expression of everyday life, or souvenir? Kevin Sudeith, courtesy of WarRug.com, CC BY-SA

Some of the rugs are artistic, and all express the historic craft of the region. But I see it as a market response to westerners looking for souvenirs more than the "artistic expression" of destitute women that the Times would have us believe.

Of course, I've become more skeptical with every passing year of what I read in any news source.

Elias describes himself as “a specialist in the visual and material culture of the Islamic world.” Should I trust his take over the Times and Dr. Hutton?

I found Elias compelling. Duh -- why would I see these “war rugs” as an organic expression of Afghan culture, anymore than a four-inch Statue of Liberty replica bought at the JFK airport expresses American culture?

But there's more. Here's where Elias's account won me over, and why I felt this was worth sharing with you.

Elias characterizes the “war rugs” as a “trauma market":

Implying that rugs are a source of income for traumatized and destitute Afghan women ignores the reality that the overwhelming majority of profits go to middlemen and dealers. A work-from-home model encourages workers to devote all available time to rug production. It also encourages child labor: Children are either tasked with making the crude rugs or are forced to take up the responsibilities of adults.

The appeal of war rugs – and the insistence that their designs represent a victim’s experience of war – seems to reflect a vicarious desire to peer into the emotional experience of Afghan civilians.

In reality, though, this gives primacy not to the actual experiences of Afghans, but to the viewers’ and customers’ ideas of victimhood. The granular realities of the loss of home and animals, family deaths or food insecurity aren’t represented in the rugs. Nor should we assume weavers would wish to put their own traumas on display for the world.

Modern rugs are not venues for self-expression, and the designs tend to contain an index of symbols that reflect an outsider’s understanding of war: AK-47s, 9/11, security politics and drones.

Nowhere in the rugs do we see the well-documented psychological and health impacts on Afghanistan’s population caused by decades of deprivation and violence.

Real trauma is not only hard to turn into a commodity, it is also hard to live with – even in souvenirs.

Why is there so much human suffering in the world in 2023? Why do wars and widespread poverty persist?

I submit the trauma market as a small part of the answer. If well-meaning people can consume human suffering as a commodity in one instance, it could happen elsewhere.

Buyers of those rugs felt that they were celebrating the artistic expression of "ordinary" Afghans, when the market they were supporting was exploiting those same people. I'm no better, having consumed a media narrative built on this same market.

Perhaps, when you consider the documented harm of well-meaning NGOs in the U.S. and many parts of the world, there's more to this than rugs.

In retrospect, I feel I owe an to the Afghan people I thought I empathized with. It didn’t do you any good, and narratives like this do a lot of harm.

Where do you see the potential for a "trauma market"? I'd love to hear your thoughts.

P.S. Thank you for tuning into these thoughts today. You can opt out or adjust your preferences anytime at the links below.

I'd love to keep this channel open, and to hear what you're working on. What frustrates you or excites you in your work today?