Why don’t Vermonters want to work for Phil Scott?

2024-03-05

Dear friend,

Does it bother me that constituents sometimes confuse me, Rep. Tristan Roberts of Halifax (not the one in Canada), for Rep. Tristan Toleno of nearby Brattleboro?

It does not.

Toleno is a veteran six-term Rep who sits on House Appropriations and brings an eagle eye on the workforce crisis embedded in Vermont’s 2025 budget. I’m up in House Corrections and Institutions trying to sleuth out what’s working and what’s not working in the Department of Corrections.

When the “Tristan Caucus” huddles in the State House hallway to share essential gleanings, it’s like we both got to be in two places at once.

Rep. Tristan Toleno of Brattleboro (left) and Rep. Tristan Roberts of Halifax (right) on January 4, 2023.

Photo: Kelly Fletcher

Comparing notes the other day, Rep. Toleno asked me this.

“Why don’t Vermonters want to work for Phil Scott?”

The question stopped me in my tracks. Surely Rep. Toleno was being hyperbolic, making a political dig on America’s Most Popular Governor®.

Or was he? We dove into the data.

At the mid-point of 2022, the Department of Corrections (DOC) faced a 30.4% vacancy rate and an alarming morale issue, with 30% of workers reporting suicidality. “The stress levels are putting people over the edge,” one officer reported to UVM researchers.

Now down to only 16.6% vacant, DOC has steadily filled positions after implementing its “Stability and Sustainability Plan,” a grab-bag including increased pay, recruitment incentives, and a still-controversial restructuring of shifts relying on draining 16-hour stints. With the current labor contract expiring this June, taxpayers might wonder how much they will have to pony up to continue to fill vacancies.

A tight labor market is traditionally hard for corrections, but they’re not alone. Unique applications for State jobs are down from 18,778 in 2019 to 12,690 in 2023. Almost three-quarters of all openings had fewer than 10 applicants.

Once an offer had been made, only 75.8% of applicants accepted.

Once hired, 10% of State workers don’t make it beyond 30 days at their new job, according to Gov. Scott’s most recent Workforce Report. Over 26% don’t make it to the six-month mark and 40% don’t make their first anniversary.

The overall job turnover rate for State employees is 13%—a higher rate than any year since 1998, even counting years with retirement incentives!

“Churn and burn” is how Rep. Toleno sums up what I’m calling our retention death spiral.

To compensate, Gov. Scott has shifted the entire salary distribution of State workers over the past five fiscal years. “The number of employees decreased in the lower pay ranges and increased in the higher pay ranges,” states the Workforce report. Through raises, hiring at higher salaries, and reclassifications, the average salary for a full-time employee jumped 4.5% in 2023, up to $69,699, plus benefits.

Even with those increases, vacancies in agencies like the Department of Labor illustrate the ongoing challenge. As it stands today, 54 of 264 positions there are open, or 20%.

As a legislator often asked by constituents for help when their unemployment claim gets hung up, Labor’s leadership and staff have been responsive. They’re doing their best to cope with years of deferred maintenance on their IT system. Labor’s mainframe computer system is in the midst of a $40 million overhaul that will take up to four years to complete. In the meantime, when it glitches, staff are forced to work overtime to process requests manually.

The Department of Mental Health has 116 open positions out of 308—mostly nurses. Vermont Veterans Home has 64 vacancies out of 195—also mostly nurses. The Department of Children and Families is short on almost 10% of positions. Vermont State Police has 17% of positions vacant.

Shortages like these have real impacts on Vermonters. For example, there’s a months-long waiting list for the Veterans Home, with 25 beds offline due to lack of staff.

The nursing shortage shifts essential shifts to “travelers”—temporary contract nurses who command higher hourly wages, draining budgets while not sticking around long enough to build a stronger workplace culture.

One of the reasons this crisis isn’t more evident to Vermonters is that Scott’s proposed budget books $57 million in savings from the staff vacancies. Another boost was an increase in federal Medicare money that came through because we became poorer relative to surrounding states.

Understandably, Scott didn’t highlight these points in his budget address.

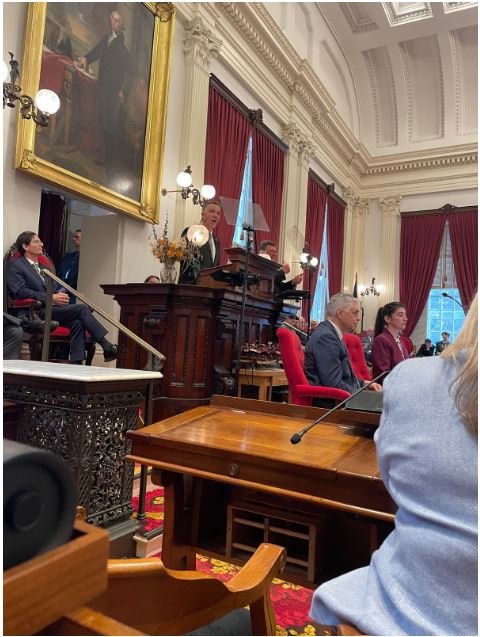

Gov. Phil Scott delivers his Fiscal Year 2025 Budget Address on January 23, 2024.

Either Scott or Vermont’s next Governor is going to need a more visionary statewide employment strategy.

We can’t pay our way out of this crisis. Take it from Nikki Fuller, Deputy Commissioner in Scott’s Department of Human Resources.

The State’s recruitment focus has been “how much more money can we give you,” Fuller told House Appropriations this month, but she says that employees are thinking differently since COVID.

“I’ve worked in government all my life,” said Fuller. “Everything in government is about getting the job done, but sometimes we forget about—How does it impact the individual?”

“People will no longer tolerate a work environment where they do not feel comfortable,” Fuller reports.

Is Phil Scott listening?